Abortion Laws Meant To 'Protect Women' Are Actually Hurting Them, Study Proves

Ohio passed a law in 2011 saying that women had to take the abortion pill using the exact FDA guidelines.

If you don't know much about medicine, that sounds reasonable. But the thing is, a lot of medicines are prescribed using evidence-based guidelines rather than the FDA's official one. Moreover, that FDA guideline was outdated from the 1990s.

To get a medication abortion in Ohio, you had to go to a doctor four times and had to take a larger dosage. It also limited the weeks into a pregnancy you could take it.

Ohio, Texas and North Dakota all have this law that says you have to follow FDA guidelines.

Fans of the Ohio law said it is about "protecting women's health." But many pro-choice advocates saw it hurting women as it made them use outdated instructions and created more barriers to access.

Dr. Ushma Upadhyay, from the Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health research group at the University of California, San Francisco, was one of the skeptics. She told Elite Daily,

I was just shocked to hear that this law could be enacted.

So she did a study, published on Tuesday in PLOS Medicine, about the effects of the law.

Upadhyay compared the results of women who had medication abortion before the 2011 law and after. Overall, medication abortion (and the "surgical" abortion procedure) are extremely safe, but can require follow-up appointments or involve side effects.

The study found those who had to comply with the law were three times more likely to need at least one additional treatment. The amount of women who needed further treatment rose from 4.9 percent to 14.3 percent.

The rate of incomplete or possible incomplete abortions rose from 1.1 percent to 3.2 percent.

And women had more side effects when they followed the law. Side effects like nausea and vomiting were reported by 8.4 percent before the law passed -- and 15.6 percent had them after.

Upadhyay said,

This law that purported to protect women's health and safety actually ended up producing worse outcomes for women.

Upadhyay's study showed the negative medical effects of this law, but there were other negative effects as well.

Because women had to take a larger dosage, it could cost them more, making it less accessible. They also had to go to the doctor four times, making it less accessible. It was also available for a shorter time into a pregnancy... making it less accessible.

Women choose a medication abortion for a variety of reasons, including it gives them more personal control over the abortion. It can also be a good option for women in rural areas without abortion providers if they can get prescribed through telemedicine.

But the amount of women seeking an abortion who chose the medication form dropped from 22 percent to 5 percent after the law went into effect.

Upadhyay said,

We have to respect women's preferences for treatment, and when there are multiple choices, women should be able to choose.

Women in Ohio, Texas and North Dakota no longer have to follow the outdated guidelines. The FDA updated their own guidelines earlier this year, following the evidence-based protocol that other providers were already using.

But if research progresses to show better, effective ways to use the abortion pill, women in those states will not be able to progress along with that -- until the FDA revises their own guidelines to meet the updates.

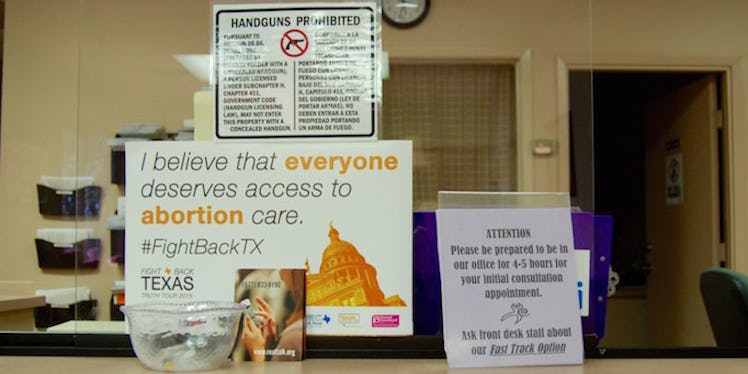

The purpose of state abortion laws is often said to be to protect women, but more often than not all they do is make abortion less accessible.

The Supreme Court struck down a law following that bad logic in Texas this summer. Ruth Bader Ginsburg made it clear this decision was based on the fact that the Texas laws did not follow medical evidence.

Upadhyay hopes her research can help show why it's important that state abortion laws actually do follow medical evidence. She said,

All abortion laws should be based on scientific research.

Thanks to the FDA guideline update, Ohio women are following current medical standards, but they'll be left behind if those standards improve before the FDA catches up.

Citations: Columbus Dispatch