This Is How Trump's SCOTUS Nominee Could Impact Abortion, According To A Woman Who's Fought For Rights

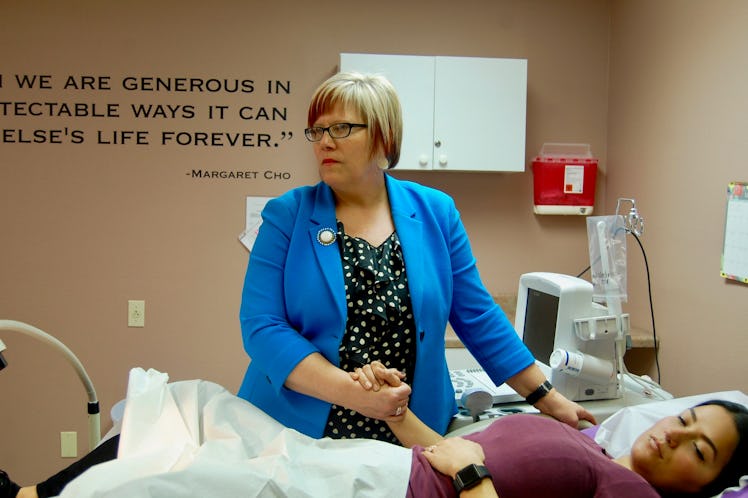

In March 2016, Amy Hagstrom Miller, the founder and CEO of Whole Woman's Health, went to the Supreme Court with one goal: to persuade Justice Anthony Kennedy to agree with her charge that a set of anti-abortion laws in Texas were an unconstitutional "undue burden" on women. Two years later, she's the lead plaintiff on six more challenges to abortion-restricting laws, any one of which could end up back at the Supreme Court, and with Kennedy's departure, President Donald Trump's Supreme Court nominee could impact Roe v. Wade, the fundamental 1973 case that declared abortion a constitutional right across the nation.

"I really felt like the part of Kennedy we could appeal to from the abortion provider side is sharing the hearts and minds of the people we serve," Hagstrom Miller tells me in an interview for Elite Daily the day after Kennedy announced his resignation. "I don’t know that any of the other conservative judges are sensitive to that stuff. I just don’t know."

For 30 years, Kennedy served as a swing vote on abortion cases — whichever way he decided would push the majority. Now, the future of abortion cases for the next generation seems certain, and it's bleak. Trump has repeatedly said he would appoint a justice who would work to overturn Roe, and unless the Senate — which is currently a Republican majority — finds a way to force him to change his mind on that, a conservative justice will be filling Kennedy's seat, leaving the liberal justices without much of a shot at a majority opinion.

Although many are saying that this could be the end of Roe, Hagstrom Miller is more measured — slightly.

"I don’t know that one man’s retirement can undo that 45 years of precedent," she says. "We saw similar things happen under both Bush and Reagan, when the Department of Justice tried to undo Roe and it went to the Supreme Court. There’s a lot of precedent, and even conservative judges seem to respect judicial precedent."

There will be some places where the chipping away will be so successful that abortion won’t exist.

Indeed, Supreme Court justices are supposed to function by following the precedent (i.e. decisions) set by previous Supreme Court decisions. The decision in Roe — that abortion is a right — is precedent. So, too, is the decision in 1992's Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which determined that laws cannot create an "undue burden" to women's access to abortion.

In 2016, Hagstrom Miller was instrumental in setting another precedent, thanks to Kennedy's swing vote. The opinion in Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt further defined what an "undue burden" is and clarified that laws about abortion should have an actual medical purpose, if that's what the lawmakers creating them purport is their function. (The Texas laws the case struck down had no medical benefit, but did, incidentally, force a bunch of clinics to shut down, restricting women's access to abortion.)

"Even if people clear the path to chip away at Roe, I think it’s going to have to go through the Whole Woman’s Health scrutiny, which is much stronger than we had a few years ago," Hagstrom Miller says.

Although Hagstrom Miller believes precedent will keep Roe in place, she does think the country will see a "chipping away" at it — and "there will be some places where the chipping away will be so successful that abortion won’t exist." Hagstrom Miller has personal experience with the "layering effect" of "chipping away" at abortion rights, as she saw it happen in Texas, where Whole Woman's Health operates several clinics, some of which shut down before 2016 due to laws. One by one, new laws were introduced, which worked to make abortion inaccessible.

"With each restriction, a group of people can’t make it in for an abortion anymore. It’s not like in one fell swoop, Roe is flipped and abortion is made illegal. It’s the 24-hour waiting period, the forced ultrasound, the two-visit requirement, then it has to be with the same doctor, then it has to be in a certain kind of building, then only a certain kind of doctor, right? With each of those restrictions, less and less people actually have access to safe abortion. It may exist on paper, theoretically, but actually obtaining it is next to impossible," she explains. "Without a full flip of Roe, [you'll get] this kind of effect where they get rid of a second-trimester abortion, and then get rid of abortion for minors… chipping away, piece by piece, the right to abortion."

There are currently many abortion law challenges in the lower courts, which gives the Supreme Court many opportunities to take something on in the near future. This month, Whole Woman's Health filed three sweeping lawsuits against abortion-restricting laws in Indiana, Texas, and Virginia, which could eventually end up in the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, Whole Woman's Health is the plaintiff on a challenge to a Texas law banning the dilation and evacuation method of abortion, which is used commonly in the second-trimester. There are also challenges against that ban in Kentucky and Arkansas. This, Hagstrom Miller has been told, is the most likely to be the next abortion case in the Supreme Court. If the conservative judges decide against the challenges, that would effectively be the end of second-trimester abortions in those states, in a chip at access that would impact the vulnerable women who typically seek second-trimester abortions.

But Hagstrom Miller isn't letting that scare her (at least, not until she sees who gets appointed), and she is remaining committed to being "a very strong and committed plaintiff" in each case and "[putting] together the best cases that we can to demonstrate what restrictions on access to abortion do to people."

"I’ve always had to be committed to doing what is right and trying to bring justice to people, whether or not it was likely for us to win. The odds were not in our favor for Whole Woman’s Health, by any stretch," she says. "But I don’t get to be in control of, ultimately, who gets to hear those cases. So it doesn’t change my commitment to do the right thing."