I Spent A Week With Syrian Refugees In Jordan, And No One Tried To Kill Me

"If you don't f*cking die in the Middle East, let's go see the new James Bond movie when you get back!"

That was the last thing one of my roommates said to me before I left for Jordan. He was being sarcastic, of course, but unfortunately there are many Americans who actually think that way -- their perception of the Middle East and its diverse array of people is deeply skewed.

"Thanks for the support!" I yelled back.

For the record, we did end up seeing the new James Bond (so I didn't die, as you might've guessed).

The morning I departed for my big adventure, I was admittedly a little hungover. The night before, I had dinner (and drinks) at Lexi Shereshewsky and Demetri Blaisdell's apartment in Manhattan.

I was about to travel to the Middle East with this couple, and they were basically complete strangers. The libations were a much-needed icebreaker.

Their apartment was impeccably decorated, full of items from their well-traveled lives. They had the most eclectic array of photos and artwork adorning their walls.

They were immediately likable -- obviously cultured and well-educated, but not at all pretentious about starting their own NGO, The Syria Fund, before turning 30.

But I wasn't just at their apartment to drink and fraternize, I was also there to pick up a bag full of supplies for Syrian refugees -- mainly winter clothes for kids.

I woke up a little late the next morning, chugged some water and hastily gathered my luggage (the monstrous bag of donations included) before heading to JFK.

When I arrived at the airport, there was no one in line to check in. "Must be my lucky day," I thought.

I was wrong.

I was five minutes late to check-in and missed my 11 am flight. The plane wasn't even boarding yet, but they still wouldn't let me through.

There was a brief period of despair in which I stared at the bag in my arms and worried my unpunctuality would result in Syrian children not getting winter clothing. Fortunately, I worked it all out and got on the next available flight.

At around 4 pm, I was finally on my way...

Early one Tuesday morning, a coworker forwarded me an email. It was written by Lexi, who was looking for donations for her upcoming trip to Jordan with The Syria Fund to help refugees.

I'm happy to donate, I thought, but I also want to go. I'd been writing about the refugee crisis for months and wanted to learn about it firsthand.

At the risk of coming off as crazy, I replied asking if I, a total stranger, could tag along. Around ten minutes later, Lexi simply responded: "WOW. Can you meet around lunchtime?"

After a brief meeting and a subsequent brunch on the Lower East Side, she and Demetri agreed to let me join them. One week later, I was on my way to spend a week in the Middle East.

The journey was long, and I had an about six-hour layover in Dubai, which was unlike any airport I'd ever been in before. I first found myself sipping on a latte at Starbucks, followed by beers at a Heineken bar, followed by a meal at Burger King.

I eventually fell asleep on one of the airport chairs, only to be woken up by the deafeningly loud call to prayer. After wiping the nap-induced drool from my face, I finally boarded my flight to Amman, Jordan's capital.

I arrived in Jordan just after midnight. I'd been traveling for nearly 24 hours and looked and felt like a zombie.

The driver I'd scheduled to pick me up was named Mohamed. He spoke perfect English. I didn't speak a word of Arabic. He told me to sit in the front seat, and we set off for the hostel I booked a room in.

In my travel-weary daze, it hadn't really struck me I was in the Middle East. It was dark and felt no different from driving home from an airport back in the US. The only noticeable difference was the billboards had advertisements in Arabic instead of English.

As we drove along, Mohamed pointed out an enormous shopping mall on the left. It looked exactly like one you'd find in an affluent American suburb. To the right, he pointed to old Jordanian houses stacked on the hillside.

"New Jordan and old Jordan," he said, shifting his gaze from side to side.

We finally arrived at the hostel and dragged the enormous bag and my other luggage up to the front desk.

As I checked in, there was a diverse array of people sitting on couches behind me drinking and singing, primarily in Arabic.

There seemed to be people from all over the world involved in this little sing-along. If I'd been there on vacation, I definitely would've joined in the revelry. But I knew I had a long day ahead of me, and an even longer week, so I forced myself to bed.

I awoke early the next morning and made my way to the Airbnb where Lexi, Demetri and our other travel companions were staying, walking past children playing, men smoking cigarettes on the corner, women in burqas and others in jeans and t-shirts, hookah bars where soccer highlights were blasting on TVs, restaurants and small shops.

The route took me down Rainbow Street, one of Amman's most famous thoroughfares.

Lexi was waiting for me on her corner and quickly led me inside to meet the rest of the group. The first thing that struck me was the view from inside the apartment. Through its kitchen windows, I truly saw Amman for the first time.

There were buildings littered along hills and stacked on top of one another for what seemed like miles. Ancient Roman architecture, mosques and modern skyscrapers all met under an endlessly blue sky. It was absolutely beautiful.

Inside the apartment, I finally met our other travel companions: Ken, a worldly lawyer from Connecticut, Robin, Ken's hilarious half-brother from Las Vegas and Sarah, Lexi and Demetri's college friend who currently lives in Cairo, where the three of them studied abroad.

It was in Cairo that Lexi and Demetri began their romance, which eventually led them to live in Syria for two years. As they fell in love with each other, they also fell in love with Syria and the surrounding region.

They left in late 2010, not long before things got really bad. All of this is ultimately what led them to establish The Syria Fund.

As the conflict in Syria escalated, Lexi and Demetri were heartbroken to see violence, destruction and despair destroy a place they'd once called home.

As Lexi put it,

It has been really difficult to watch this country that we loved and lived in fall into such despair. I always say that the Syria of today isn't the Syria that we knew, but the Syrian people are. At a point, it became impossible to keep watching the news without doing anything.

Alongside local partners, The Syria Fund provides material support to Syrian refugees, focusing especially on those living in urban areas. But it goes beyond that.

Demetri and Lexi are committed to bridging the cultural gap between the West and the Middle East, and helping to humanize Syrians for people who might have distorted notions of what Arabs are really like.

As Demetri explained,

For me, The Syria Fund is almost as much about changing perceptions as it is about helping those in need. The almost year and a half I spent living in Syria was one of the best times in my life. Since the war has begun, colleagues and acquaintances in the US tend to ask me about the violence, about the Islamic State, or about whether any solution can be reached. But each time I have those conversations, I think about what a wonderful place it was to live and the amazing people I met there.

It's because of people like Lexi and Demetri refugees in urban areas are getting the help they need.

I met a refugee we'll call Hunter not long after I was introduced to Ken, Robin and Sarah. He asked me not to use his real name out of concerns for his safety, but since he used to hunt rabbits in Syria, "Hunter" felt like an appropriate nickname.

Hunter is in his early 30s and originally from Palmyra, Syria.

He's about 5' 9" and has a small but oddly endearing pot belly -- he looks like a man who can get a hard day's work done but appreciates good food at the end of it. His seemingly permanent smile masks the unspeakable horrors that occurred to both him and his family in Syria.

On the second day of the trip, I was sitting in the passenger's seat of a rented four-door sedan that reminded me of the beat up but ever-dependable Corolla I drove in college. Hunter was driving, Ken and Robin were in the back seat.

We were headed toward Azraq, Jordan, a city about two hours away from Amman, where a large number of Syrian refugees now live.

The traffic on the way there was insane, as it was throughout the week. There seem to be no rules to driving in Jordan -- you just force your way through it all and hope for the best.

Throughout the drive, Hunter blasted Arabic pop music on the radio. He told me most of it was Egyptian. It sounded like American pop music, hip-hop and the Arabic language had a musical baby. I liked it, even though I had no idea what it was about.

As we drove through Amman, Hunter pointed out sites of various importance. It felt odd a Syrian refugee was playing the role of tour guide in a country that was not his own while driving us to see other refugees.

At one point, we drove past the Syrian embassy, where it seemed hundreds of people were in line outside.

"They are waiting for new passports," Hunter said.

As we reached the outskirts of Amman, where there were fewer buildings and the desert could be seen in the distance, Hunter showed me a scar on his wrist.

He explained it was from several years earlier, when the Syrian police arrested him, detained him for 10 days and tortured him.

They beat him and broke his hand, which ultimately required two surgeries and led to the scar.

Hunter's only "crime" was looking similar to a suspect for whom they were searching. They'd arrested him by mistake.

This occurred before the war that split his family apart and caused him to flee south to Jordan. It was before ISIS beheaded his uncle and cousin, shot his brother (who's fortunately still alive), decimated his city and took his house.

"My family was destroyed, no one has seen anyone in a long time," he told me. "Hypothetically, if the war ended tomorrow and there was peace in Syria, would you return to Palmyra?" I asked him. He replied without hesitation, "No. There is nothing for me there now."

The casual nature with which he told me these things was almost as shocking as the content of our discussion.

Violence, death and destruction have become normal aspects of the lives of far too many Syrians. The brutality of ISIS is indiscriminate. It frequently kills civilians, regardless of age, gender or religion.

In the States, we typically only hear about ISIS's barbarism when it's directed at Westerners, but Syrians experience it on a daily basis.

We often forget the most common victims of Islamic extremism are Muslims.

If Syrian civilians aren't being killed by the Assad regime, they're dying at the hands of ISIS.

The ongoing war in Syria has claimed over a quarter of a million lives and displaced around 12 million people. There are close to 8 million internally displaced Syrians and more than 4 million Syrian refugees.

At present, there are around 19.5 million refugees across the globe, making this the worst refugee crisis since World War II.

One out of every 122 people is a refugee, and Syrians make up the majority.

Many of us tend to think of refugees as people living in massive, depressing camps full of anguish and despair.

While there's some truth to that, most of the Syrian refugees in Jordan (around 80 percent) are living outside of UN-run camps. In other words, they're fending for themselves.

The seven days I spent in Jordan felt like weeks. I saw, heard and learned more than I ever anticipated. But it didn't feel like enough time to fully comprehend the scale of the ongoing Syrian refugee crisis. And, the truth is, it wasn't.

Months later, my thoughts are still consumed by the experience.

One thing that's particularly hard to forget is all of the children we met and encountered during our time there.

Around 41 percent of all the world's refugees are children.

Education is one of the forgotten casualties of war. Most of the children we encountered in various parts of Jordan were several years behind in their schooling.

The Syria Fund is committed to helping Syrian children catch up on the schooling they missed, so we interacted with many of them during the trip.

When we finally got to Azraq on the second day, we visited a small school compound where a number of Syrian children were being taught.

Since the conflict in Syria began, the population of Azraq doubled from the influx of refugees.

The local population is around 10,000, but they now live alongside close to 8,000 refugees. And around 20,000 Syrians live in the Azraq refugee camp run by the UNHCR.

Azraq was somewhat of a ghost town. It felt like something out of an old cowboy movie. There were people there, but I saw hardly anyone outside. I can't really blame them, though, given how hot it was.

It didn't take that long to get there, maybe two hours or so, but the landscape on the way was unlike anything I've ever seen -- desert for days.

Jordan's desert is barren, flat and dark brown.

At one point on the drive, I saw a man herding sheep in the distance. "How the hell can anything survive out here?" I thought to myself.

And there's so much dust. The bag I used for the trip still has dust in it and it's nearly impossible to get off your clothes.

As we got closer to Azraq, we also saw a large military base along the road. I'd later learn this was an airbase, and yet another reminder of the war occurring to the north.

Soldiers occupied outposts every 100 yards or so. I saw several large signs with warnings written in Arabic I couldn't read, but I got the memo from the image that accompanied the words -- a camera with an X drawn through it. No photos.

When we finally arrived at the school compound, which seemed to be on the outskirts of town, we were greeted by the smiling faces of Syrian children.

They were learning in trailers, much like temporary classrooms you see at schools in America. In some rooms there were older children learning among much younger ones.

Lexi, Demetri and Sarah, who all speak Arabic, spoke with the children in gentle voices.

This meet-and-greet was followed by a plethora of photos and selfies. These kids might be refugees, but that doesn't mean they don't love technology.

No matter where you go in the world, young people are intrigued by smartphones.

At one point, three girls sitting on wooden stairs leading to a construction project on the roof motioned for me to snap a photo. When I showed it to them, they giggled uncontrollably.

This was my first encounter with Syrian children, but it would hardly be the last. They had the hearts and enthusiasm of children, even though they'd been robbed of the ability to live normal childhoods.

This is what we forget amid all of the horrible statistics and debate and fear surrounding refugees -- they are just like us, except war has changed their lives irrevocably.

On the fifth day of the trip, we found ourselves drinking tea with a group of refugees living in tents in the middle of the Jordanian desert. We'd just helped them construct a semi-permanent tent that would serve as a classroom for children in their community.

We were near North Zaatari, and probably around 15 km from the Jordanian-Syrian border.

If I'd ventured away from the camp and traveled directly north, I would've been in the middle of a war zone before long. But that fact was far from my mind as I stood there sharing an incredibly peaceful moment with complete strangers, half a world away from home.

I had to remind myself it wasn't peace that brought me together with these people. They were in that place because of an ongoing war that's claimed far too many lives already.

These people were just a dozen or so of the millions of Syrian refugees scattered across Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey and now spreading into Europe.

They had little to nothing, but still made a point to take the time to offer us tea and make us feel welcome.

As we drove away from their tiny camp in the desert, I couldn't help but think about how unfair it was I'd be returning to a privileged existence in New York City several days later while they'd continue to face a situation most can barely fathom.

No one chooses to be a refugee; it's a matter of survival. At our core, we all desire peace and stability, and the chance to build a prosperous life for ourselves and those around us. That is what refugees, from Syria and elsewhere, are searching for: a chance.

The word "refugee" is derived from the word "refuge," which means "a condition of being safe."

Who are any of us to deny another human being the right of seeking safety?

But these sentiments have often been lost in discussions of refugees, particularly in the United States. General fear of the Middle East, Arabs and Muslims has led people to stigmatize Syrian refugees as terrorists in disguise. But they're not terrorists... they're running away from terror.

In the US, where people fear Islam and events like the Paris attacks have led people to fear refugees, there's an assumption people in the Middle East hate Americans. But that couldn't be further from the truth.

When I asked Lexi what she loved most about living in Syria, she said,

As a foreigner, people always wanted to make sure that I was being treated well, and more importantly, eating well. It was rare that I would go out for the day and not get at least one completely genuine invitation to dinner. I still experience this now when I visit Syrian families in Jordan. Even when they have so little to offer, they make sure you have tea or coffee.

Although I haven't spent nearly as much time in the Middle East as Lexi or Demetri, I can confirm the people there epitomize hospitality.

The worst part of being a refugee, beyond fleeing war and being separated from your home and family, is the uncertainty.

The threat of deportation looms large over many of the Syrians populating Jordan. At the same time, however, thousands are returning home on a monthly basis because of the poor quality of life for refugees in Jordan.

Halfway through our week in Jordan, we visited Zaatari refugee camp, run by the UN's refugee agency (UNHCR).

At Zaatari, Gavin White, an external relations officer for the UNHCR, told us close to 2,000 Syrians were leaving the camp and returning home every month.

This is how bad things have gotten. These refugees would rather risk their lives and return to a country consumed by war than live in limbo in the camp.

Returning to Syria could mean death at the hands of ISIS or from barrel bombs dropped by the Syrian regime, among other terrible but unfortunately plausible circumstances.

But one can hardly blame them as they can't get work permits in Jordan and the conditions in Zaatari are hardly ideal.

In Jordan they have safety, but what use is that without the ability to build a future?

As one Syrian told me, some young men are returning to join ISIS solely because it pays fairly well. They aren't extremists, they're just desperate.

At Zaatari, we learned the UNHCR only has around 50 percent of the funds it needs to truly provide for all of the refugees in the camp. As White put it,

If you don't invest in the camp and Jordan... the scale of the crisis in Europe is only going to get worse.

In other words, if you don't want Syrian refugees heading to Western countries, assist them in the countries where the majority reside: Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey.

The most startling aspect of Zaatari was its sheer size -- around 80,000 people live there. A year before, around 110,000 people called the camp home.

But, within the camp, people are making the best of a terrible situation and life moves on in its own way.

As many as 10 babies are born in the camp per day. There is a hospital, basketball courts, a community center and more than 80 mosques.

There's even a bustling marketplace with everything from bridal shops to restaurants.

We actually stopped to eat lunch at the market, where teenagers ran up to us and shouted, "Hi, how are you," with enormous grins on their faces.

The entrepreneurship of the Syrians who organized it was inspiring.

Zaatari has only been around since July 2012, and now it's really more of a city than a refugee camp.

The camp is a sea of prefabricated houses surrounded by walls and barbed wire fences. It's very prison-like and quite daunting to enter.

For some of the children there, Zaatari is the only home they've ever known -- they have no memory of Syria.

Much of the camp is comprised of youngsters. According to the UNHCR, over half of Zaatari's population is under 18.

No child should be forced to grow up in those conditions.

Refugee camps are not meant to be permanent solutions, but with so many people there, it was hard to imagine Zaatari's sudden disappearance. This is emblematic of how long the conflict in Syria has gone on, and how unlikely it is to end any time soon.

Exactly three weeks after I returned home from Jordan, the Paris terror attacks occurred. France's beautiful capital was maliciously attacked by a vicious group of cowards and 130 people lost their lives. It was an absolutely devastating day.

Almost immediately, people began to blame Syrian refugees for what occurred. A passport was found near the dead body of one of the attackers. Even though it was confirmed fake, and none of the attackers were Syrians, many have continued to view refugees with disdain and suspicion.

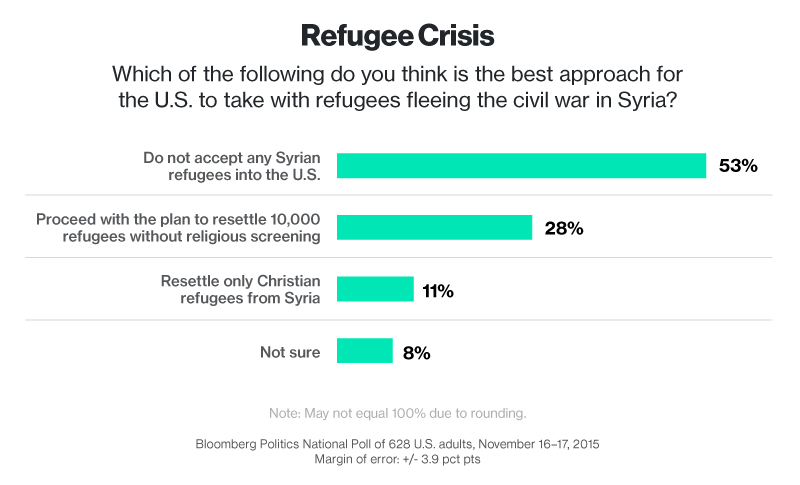

In September, a narrow majority of Americans supported President Obama's decision to accept more refugees.

Following the Paris terror attacks, however, a majority of the American public and many American politicians do not want to accept any more Syrian refugees whatsoever.

The San Bernardino attack, which occurred not long after the Paris attacks and was also linked to ISIS, further exacerbated fear of refugees and Islamophobia.

A few months ago, the image of a dead Syrian child on a Turkish beach broke the world's heart. Afterward, the US suddenly seemed mobilized to do something about the worst refugee crisis of our era.

Now, due to the actions of ISIS, a prime culprit in the refugee crisis, Americans want to turn their backs on some of the globe's most at-risk people.

Having just visited with refugees and witnessed their suffering firsthand, I can't begin to express how frustrating this is.

I am watching my country give the terrorists exactly what they want: actions motivated by fear.

They want us to fear them, they want us to fear Muslims and they want us to fear refugees. They want us to get bogged down in lengthy and costly conflicts. They want us to attack Muslim countries and ignore the plight of refugees.

ISIS hates the refugees more than anyone. Central to the terrorist organization's recruiting efforts is the idea they've created an Islamic utopia. Correspondingly, ISIS wants the world to believe the West is at war with Islam.

But when Muslims (Syrian refugees) are seen running away from ISIS and the hell it's brought about in their country, it completely debunks the notion ISIS has established an Islamic haven. And when countries like America are seen helping Muslim refugees, it invalidates ISIS's claims there is a clash of civilizations between the West and Islam.

Simply put, helping refugees hurts ISIS. It's both the ethical and practical thing to do and it must be part of America's larger strategy against these terrorists.

I understand people are scared. The wounds of 9/11 and the Boston Marathon bombings, among other incidents, are still fresh. But we can't allow fear or terror to dictate our interactions with the wider world.

There are 1.6 billion Muslims across the world. The vast majority of them do not condone the horrific actions of terrorist organizations like ISIS. Terrorism and Islam are not synonymous.

But nearly 30 percent of Americans view Islam as an inherently violent religion.

It appears as though many in this country assume all Muslims hate the US and seem to imagine people in the Middle East are constantly screaming, "Death to America!"

In my experience, this perception is completely at odds with reality.

Not once was I singled out in a negative way for being American while I was in Jordan. And I interacted with people from all over the Middle East and the Muslim world: Jordan, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Algeria and more.

In fact, most people were excited to meet an American. I had one taxi driver in Amman tell me with great pride how his aunt opened a restaurant in Wisconsin. Another was ecstatic to meet someone who lives in New York City and spoke about how badly he'd like to live there.

There are certainly dangerous parts of the Middle East right now, and I would hardly recommend anyone travel to Syria or Iraq anytime soon. But every region and every country has negative aspects.

We need to dispel the notion people in the Middle East are "others," and stop painting the entire region with one brush.

The attacks in both Paris and San Bernardino were inhumane, but the way to respond to such events is by acting humanely and rationally.

Equanimity, unity and compassion are the complete opposite of what the terrorists desire.

This is precisely what France is doing -- it's still accepting refugees in the wake of this tragedy. In fact, it's accepting even more refugees than it previously agreed to. In September, the French government said it would accept 24,000 refugees. Now, France is going to accept 30,000.

By making the decision to continue to accept refugees, France is sending a powerful and defiant message to ISIS.

It's letting these terrorists know it will not be bullied. It's committing to the ideals it espouses: liberty, equality, fraternity. America should follow in its footsteps.

France has certainly not been perfect in its response to the refugee crisis, but it hasn't turned its back on what's happening either.

The Statue of Liberty was gifted to the United States by France. It stands as a symbol of America's immigrant past and the fact millions viewed this country as a place of refuge for centuries.

On the lower pedestal of the statue, there's a plaque engraved with a poem by Emma Lazarus, a New Yorker of Portuguese Sephardic descent. The poem, "The New Colossus," was inspired by work Lazarus did with Jewish refugees on Wards Island. It reads,

Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

Indeed, one of the most powerful and famous symbols of America is enshrined with a poem expressing solidarity and empathy toward refugees.

Will we stand by these words, or we will shut our door on some of the world's most vulnerable people because we've chosen the path of fear? If we choose the latter, we can no longer call ourselves the "home of the brave."

Videos via The Syria Fund. All photography shot on an iPhone by the author.

If you'd like to donate to The Syria Fund please visit: The Syria Fund