Here's What Net Neutrality Means & Why Everyone's Talking About It

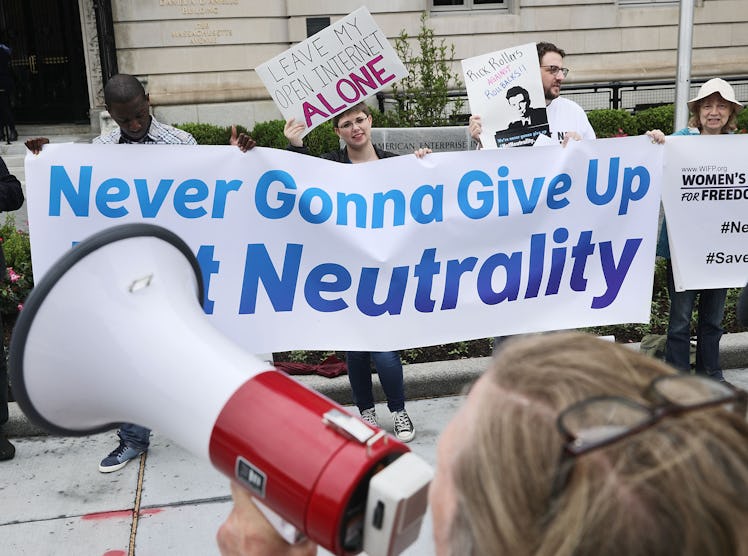

If you've hopped on the internet at least once in the last 30 days, chances are you've come across two words: net neutrality. It's no mystery why, either, since President Donald Trump's head of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) announced a plan to roll back net neutrality regulations that were put in place by former President Barack Obama's administration in 2015. Naturally, social media has been filled with arguments for and against the regulations, but neither of those are more important than the most basic question at hand: What exactly is net neutrality?

Net neutrality is a principle in favor of keeping the internet open to all users and services — and at equal speeds. Those in favor of net neutrality argue that regulations are needed to keep internet service providers (ISPs) — like Verizon and Comcast, for example — from having the power to block, slow down, or speed up traffic to different websites or services that they choose — such as Netflix or Hulu.

Here's how the FCC's official website breaks it down:

Sometimes referred to as "net neutrality," "Internet freedom" or the "open Internet," these rules protect your ability to go where you want when you want online. Broadband service providers cannot block or deliberately slow speeds for internet services or apps, favor some internet traffic in exchange for consideration, or engage in other practices that harm internet openness.

In November 2014, former President Obama asked the FCC to adopt new rules that would ensure the internet remains open. More specifically, Obama asked that the FCC reclassify internet service as a public utility so that it could be regulated as such. Obama also asked that regulations be extended to mobile internet providers.

"To put these protections in place, I'm asking the FCC to reclassifying internet service under Title II of a law known as the Telecommunications Act," Obama said at the time. "In plain English, I'm asking [the FCC] to recognize that for most Americans, the internet has become an essential part of everyday communication and everyday life."

Upon receiving the request, then-FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler appeared to show concern about the consequences of creating restrictions on how ISPs do business, even if the restrictions were made in the name of an open internet.

Months later, however, Wheeler granted Obama's request. In March 2015, the FCC's board of five commissioners voted to install net neutrality regulations by a 3-2 vote. Weeks after the vote, the board released a 313-page document detailing the regulations.

"Threats to Internet openness remain today," the document read. "The record reflects that broadband providers hold all the tools necessary to deceive consumers, degrade content or disfavor the content that they don’t like."

One of the two members of the board that voted against the rules was Ajit Pai, a Republican who argued in a statement at the time, "the American people are being misled about President Obama's plan to regulate the Internet." He continued, "Last week's carefully managed rollout was designed to downplay the plans of a massive intrusion in the Internet economy."

After the election of Donald Trump, Pai was elevated to the role of FCC chairman, with another Republican replacing his former seat on the board. Now, with a 3-2 Republican majority, Pai is in a position to roll back Obama-era regulation with a vote. On Tuesday, Nov. 21, Pai announced his intention to do just that, unveiling a plan to repeal the net neutrality rules.

Pai's proposal turned attention to mid-December, when the FCC is set to vote on the plan. Though different groups and tech companies, like Facebook and Google, have argued against imminent change, the Republican majority on the board all but assures success for Pai.

In other words, now that you know what net neutrality is, you'll soon be saying goodbye to it, or, at least, President Obama's version of it.