The Price Of A Story: The Dangerous Face Of Modern Journalism

Every morning, I spend at least 30 minutes browsing through Flipboard on my iPad, and between sips of espresso, I’ll often read an article entitled something along the lines of “Scientists Provide 7 Techniques to Be More Mindful.”

After this piece, I’ll catch up on international affairs and read an article entitled something like “ISIS Steps Up Defenses in the Province of Damascus.”

And before I leave for work, I’ll have touched upon two modern facets of journalism: The online digital age of information, such as in the form of clickbait and news regurgitation, and traditional forms of journalism reporting international stories from around the world.

Trained conflict journalists immersed into war zones provide some of these stories. They represent an increasingly limited source of individuals, who dedicate and risk their lives to bringing the truth from the heart of war to my glowing iPad screen.

Although there is nothing wrong with “7 Techniques to Be More Mindful” or “You Won’t Believe What This 10-year-old Said!” the men and women donning uniforms and banners with the word PRESS in large letters, the people caught in the central hordes of conflict, are risking their lives to tell a story of the horrors and the triumphs they have witnessed in the world’s most hard-to-reach places.

The modern dangers facing journalists carry an endless and troublesome lineup of profound issues.

The risks posed to journalists in the places where we need them most limit the quality and depth of the stories we are able to receive.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), there have been 1,121 journalists killed since 1992. In 2015 alone, CPJ reports 19 journalists who were killed by means of a confirmed motive.

Beheadings of journalists, according to president and CEO of The Associated Press (AP) Gary Pruitt, are “bloody press releases.”

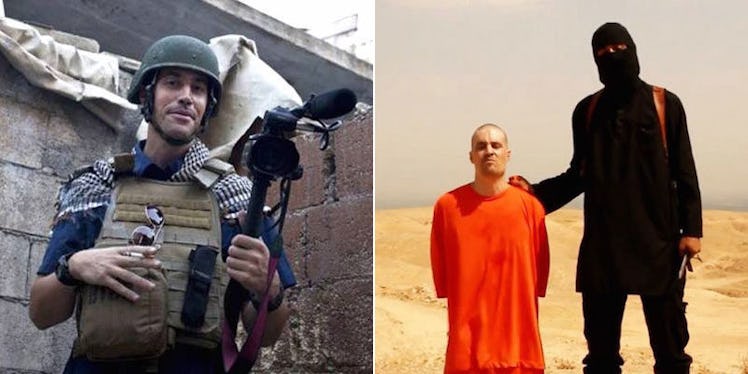

People around the world, for example, witnessed the gruesome murders of James Foley, Steven Sotloff, Kenji Goto, Anja Niedringhaus and many others.

Speaking with Elite Daily, Joel Simon, the executive director of CPJ, stated:

The last three years have been the most deadly for journalists we’ve ever documented, and two of the most deadly conflicts are the Iraqi War and the Syrian conflict, which is ongoing.

Which is why on Monday, March 30, Pruitt and AP called for changes in international laws to make the murder or kidnapping of a journalist a war crime.

"It used to be that when media wore PRESS emblazoned on their vest, or PRESS or MEDIA was on their vehicle, it gave them a degree of protection because reporters were seen as independent civilians telling the story of the conflict,” Pruitt said in a speech at Hong Kong’s Foreign Correspondents’ Club.

Pruitt goes on to say that the PRESS labeling now turns the journalist into a target, and that extremists groups don’t need media organizations to deliver a message.

These groups, such as ISIS, fully utilize social media and the Internet, and according to Pruitt, "They want to tell their story in their way from start to finish with nothing in between, and a journalist is a potential critical filter that they don't want to have around.”

The rest of the world, however, needs to hear the reports coming out of conflict zones. We need journalists to get the real facts, true stories and an unbiased look at what is happening on both sides.

Since the invasion of Iraq, reporting on world affairs has become increasingly dangerous, and although journalists were sometimes killed during conflicts and wars in the 20th century, there are several elements that have altered the role and perceived value of the journalists.

As Simon puts it:

The primary thing that kept journalists safe in conflict zones, though they were never perfectly safe, was their utility to all parties in the conflict.

Because if you are a participant in a conflict and you wanted to communicate with the population domestically, regionally or globally, the media were your conduit.

Certainly journalists were killed. This is not a new phenomenon.

But the technology that’s been developed in the last 15 years has allowed participants in the conflict to circumvent the media and communicate directly with the populations they were trying to reach.

Social media, like Facebook and Twitter, and the Internet at large has opened up unprecedented informational pathways.

Because of our modern technologies, I once put myself in the middle of a tear-gas-frenzied police vs. citizen conflict in the Bardo neighborhood of Tunis, a city in Tunisia.

I watched as protestors threw large rocks at police, and the police returned fire by shooting tear gas canisters at eye-level. I saw people pour Coca-Cola on their faces to eradicate the tear gas burns.

Although I was never in any real danger, I found the situation widely exposable because I could blog about it, write a freelance piece about the situation and possibly get it published.

And this is exactly what, according to Simon and many others, also contributes to the spike of journalist fatalities and kidnappings in recent years: the widespread distribution of freelancers in conflict areas.

In September, Allison Shelley of the LA Times wrote about the how the lack of resources for freelancers has contributed to greater dangers in the field.

Although many organizations, such as Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues, provide conflict training to independent journalists, news organizations do not provide an obligation for getting a journalist out of a life-threatening situation.

In the article, Shelley also discussed how a well-respected news organization offered her an assignment regarding the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone. When she asked about an emergency medical evacuation protocol, the organization stated, “Our company policy doesn’t cover freelancers.”

Oh, and it is important to note: Foley and Sotloff were both freelancers as well.

Fortunately, and in response to the rise of freelance deaths, AP has endorsed guidelines for freelancers that calls for them to be treated in the same way as full-time staffers.

In some cases, however, untrained (and well-respected, trained) freelancers do not fully account for the dangers posed by the changing face of war and the perceived value of journalists on the field.

Sherry Ricchiardi, a senior contributing writer of the American Journalism Review (AJR), detailed the story of Deborah Amos, who covered the Iraq war after 2003, and the extreme dangers journalists face in a 2006 piece titled “Out of Reach," writing:

Before leaving the protected walls of her living quarters, Amos took special care to make sure she didn't look too foreign or Western. She had to blend in and adhere to cultural nuances (such as remembering that some conservative Muslim women avoid eye contact with drivers and pedestrians on the street) to convince the local population around her that she was not press.

Amos repeatedly noted which cars might have been following her. She knew journalist spotters were everywhere, and everyone from the boy selling newspapers to the beggar could report to assailants a “soft-target” was on the move.

Every day, journalists in Iraq face a gut-wrenching decision: Do they venture out in pursuit of stories despite great danger or remain under self-imposed house arrest, working the phones and depending on Iraqi stringers to act as surrogates?

The ecosystem of information in conflict zones, which has always existed since the advent of modern journalism, depends on a whole team to put a story together. These teams include local journalists and translators, or “fixers.”

And often, the famed international journalist, who is on camera or has the byline, receives information transmitted to his or her hotel room, secure location or even outside the country of conflict.

The news you and I receive, however, can be profoundly affected by the lack of journalistic boots on the ground.

Compared to earlier conflicts, Simon notes:

Journalists used to keep themselves safe in conflict by identifying themselves.

In many parts of the world now, journalists are simply targets, so identifying yourself makes you an easier target. And that’s completely transformed the way international journalists work in these environments.

Furthermore, in this new environment of journalism we have to ask ourselves: How trustworthy is the information we are receiving?

The greater emphasis placed on the safety and value of journalists, coupled with the widespread information ecosystems available in conflict zones, coupled with the massive increases of technology available all contribute to the future direction of journalism. And I’m an optimist.

As we've seen, journalism has the capacity to both reduce and incite conflict.

The perceived value of professional journalists, whether traditional or freelance, illuminates and reflects upon a much greater need in this globalized world, where the true reporting of events on the ground affect international communities, and thus, the conflict themselves.