The word "priority" didn't always mean what it does today. In his best-selling book, "Essentialism" (audiobook), Greg McKeown explains the surprising history of the word, and how its meaning has shifted over time:

The word 'priority' came into the English language in the 1400s. It was singular. It meant the very first or prior thing. It stayed singular for the next 500 years. Only in the 1900s did we pluralize the term and start talking about priorities. Illogically, we reasoned that by changing the word, we could bend reality. Somehow, we would now be able to have multiple 'first' things. People and companies routinely try to do just that. One leader told me of this experience in a company that talked of 'Pri-1, Pri-2, Pri-3, Pri-4 and Pri-5.' This gave the impression of many things being the priority, but actually meant nothing was.

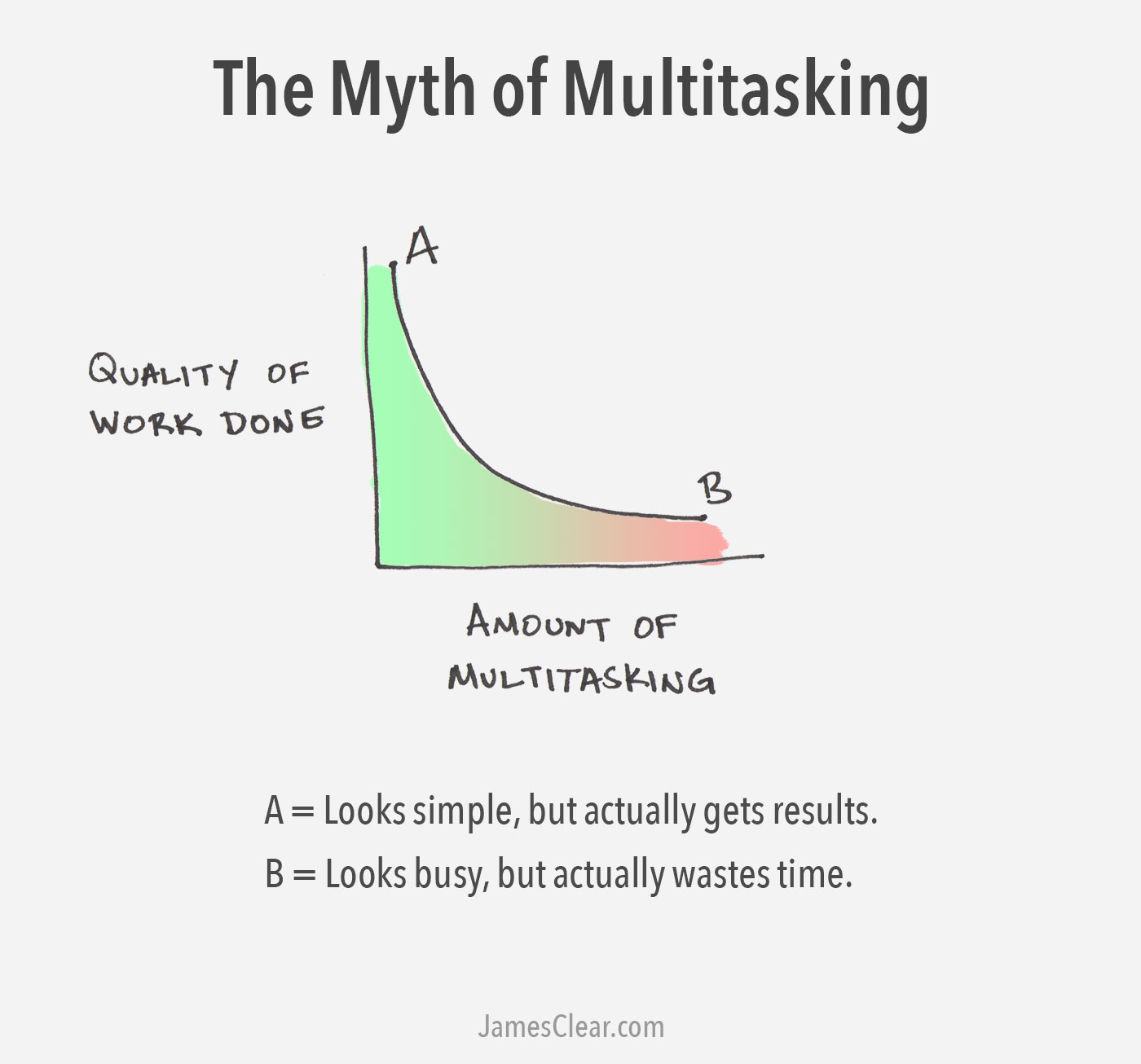

The Myth Of Multitasking

Yes, we are capable of doing two things at the same time. It is possible, for example, to watch TV while cooking dinner, or to answer an email while talking on the phone.

What is impossible, however, is concentrating on two tasks at once. Multitasking forces your brain to switch back and forth very quickly from one task to another.

This wouldn't be a big deal if the human brain could transition seamlessly from one job to the next, but it can't. Multitasking forces you to pay a mental price each time you interrupt one task and jump to another. In psychological terms, this mental price is called "the switching cost."

Switching cost is the disruption in performance that we experience when we switch our attention from one task to another. A 2003 study published in the International Journal of Information Management found that the typical person checks email once every five minutes. On average, it takes 64 seconds to resume the previous task after checking your email.

In other words, because of email alone, we typically waste one out of every six minutes.

While we're on the subject, the word "multitasking" first appeared in a 1965 IBM report that talked about the capabilities of its latest computer. [1] That's right. It wasn't until the 1960s that anyone could even claim to be good at multitasking. Today, people wear the word like it's a badge of honor. They act like it's better to be busy with all the things than it is to be great at one thing.

Finding Your Anchor Task

Doing more things does not drive faster or better results. Doing better things drives better results. Even more accurately, doing one thing as best you can drives better results. Mastery requires focus and consistency.

I haven't mastered the art of focus and concentration yet, but I'm working on it. One of the major improvements I've made recently is to assign one — and only one — priority to each work day. Although I plan to complete other tasks during the day, my priority task is the one non-negotiable thing that must get done.

The power of choosing one priority is that it naturally guides your behavior by forcing you to organize your life around that responsibility. Your priority becomes an anchor task. It's the mainstay that holds the rest of your day in place. If things get crazy, there is no debate about what to do or not to do. You have already decided what is urgent and important.

Saying No To Being Busy

As a society, we've fallen into a trap of busyness and overwork. In many ways, we have mistaken all this activity to be meaningful. The underlying thought seems to be, “Look how busy I am. If I'm doing all this work, I must be doing something important.” By extension, that becomes “I must be important because I'm so busy.”

While I firmly believe everyone has worth and value, I think we're kidding ourselves if we believe being busy drives meaning in our lives. In my experience, meaning is derived from contributing something of value to your corner of the universe.

The more I study people who are able to do that — people who are masters of their craft — the more I notice they have one thing in common. The people who do the most valuable work have a remarkable willingness to say "no" to distractions. They focus on their one thing.

I think we need to say "no" to being busy and "yes" to being committed to our craft. What do you want to master? What is the one priority that anchors your life or work each day? If you commit to nothing, you'll be distracted by everything.

[1] IBM Operating System/360 Concepts and Facilities by Witt and Ward. IBM Systems Reference Library. File Number: S360-36

This article was originally published on JamesClear.com.