America Is Still Gaslighting Black People About Racism

As I write this article, the sound of rubber bullets and tear gas canisters collide in my Los Angeles apartment. The cacophony of sound, echoing of death and terror, is deafening, and the non-stop din is traumatizing all over again. Downtown Los Angeles is one of the many epicenters of outrage, pain, and protest following a string of killings of Black people by the police. The horrific killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery have proved to be the last straw for long-simmering racial tensions. Black Americans are tired of being murdered by the state with impunity. Tragically, Floyd, Taylor, and Arbery are just three names in a sea of Black casualties at the hands of white supremacy and racism.

As a Black Queer woman, I process my grief by writing. Upon reading an article I wrote about Ahmaud Arbery, my grandfather — always my biggest fan — called me. “I read your latest article on police brutality and white supremacy. You’re spot on. I am so sorry for the state of this world you inherited,” he told me. “I wanted better for you. I fought for better for you.”

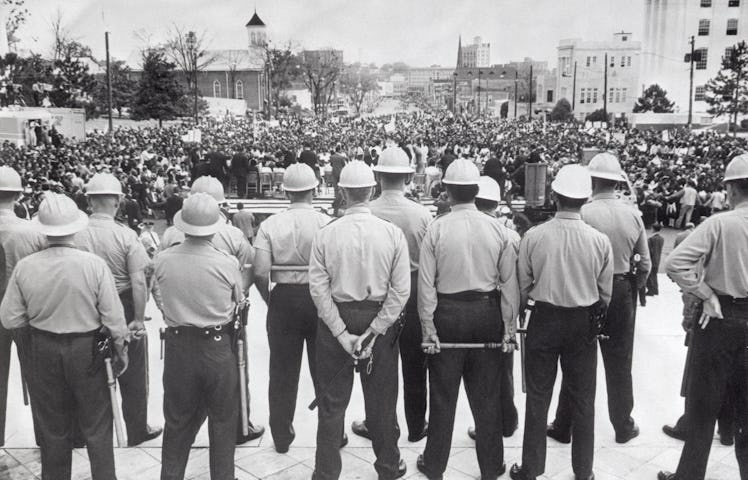

Now retired, my 78-year-old grandfather spent his life working in aviation and the military. His career took him from his hometown of Los Angeles and led him to Keesler Air Force Base in Mississippi, where he lived in the early 1960s. His time at Keesler marked a huge shift in his Black consciousness. “When we were on the base I could sit wherever I wanted, but once we left the base, I was asked to move to the back of the bus,” he recalls. “I experienced racism in California as well, but bus segregation wasn’t a law in Los Angeles.”

Racism has never gone away, and now with technology, your generation is uncovering what has always been there.

My grandpa experienced the deep racism of the American South and the insidious racism of the American West. He has lived through defining moments of America’s racial history — the Jim Crow South, the murder of Emmett Till, and the Rodney King riots. However, when I ask him if he thinks America has progressed, he says, “No.”

When I ask him if he is surprised that America continues to be deeply racist, he paints a picture for me. “In 1955 Los Angeles, I dealt with segregation,” he says. “Then, I headed to Mississippi in 1961. Prior to my departure, my mother sat me down and gave me the Emmett Till lecture. She told me to be careful. Then in 1976, I went to South Boston while working for the federal government and white people were protesting against integrating schools. And then I left for Atlanta, Georgia. Atlanta was seen as a Black oasis, but when you went outside of Atlanta, Black bodies were found floating in the [Chattahoochee] River. Racism has never gone away, and now with technology, your generation is uncovering what has always been there.” My grandfather reminded me that time and progress are not linear. For Black people in America, time is a twilight zone of horror. We remain stuck in a historical nightmare.

But he also gave me permission to feel the depth of my anguish and helped me silence my internal voice deep inside that says it's not that bad. Together, we sat in our anger and our pain.

America tells Black people, especially young Black people, that we are allowed two emotions towards our nation: forgiveness and gratitude.

Intergenerational trauma, as defined by the American Psychological Association, is a “phenomenon” in which the descendants of a trauma survivor display the same kinds of trauma reactions as the survivor themself. The historical or cultural trauma is passed from generation to generation, as survivors of the initial trauma struggle to deal with its effects, and then is compounded when the next generation has to deal with it all over again. While research into the effects of intergenerational trauma is relatively new, it can leave its marks on mental health, as well as familial, social, and cultural relationships. Black people must not only contend with our discrimination in the present, but our marginalization in the past. Racism does not stop, it leaves a legacy of both ancestral trauma and present pain that must be accounted for.

To be Black in America is to be bombarded with the notion that I, as a contemporary Black person, cannot possibly understand true racism. True racism, white America suggests, stopped somewhere around the 1950s. America tells Black people, especially young Black people, that we are allowed two emotions towards our nation: forgiveness and gratitude. Gratitude for how far things have come, and forgiveness for how terribly our ancestors were treated. America constantly attempts to gaslight Black people into believing that time and progress are linear. America uses time as a shield against culpability for systemic racism.

Nicole, 25, a Harvard graduate and former member of Black Lives Matter LA, is constantly engaged in political conversations with her family. She and her grandmother often commiserate over their shared fear of what white America is capable of.

Nicole’s grandmother was born in Hattiesburg, Mississippi in the 1930s, in a time and place where violent racism was the norm. “She has seen Black people murdered in front of her. It’s a lot of trauma,” Nicole says. Of all of her grandmother’s stories, Nicole most vividly recalls when her grandma told her that she witnessed a white bus driver shake a Black baby to death. “The baby would not stop crying,” she relates her grandmother’s tale. “So, my grandmother said, the bus driver shook the baby until [it] stopped breathing.”

Like my grandfather, Nicole’s grandmother is not easily disillusioned by tales of racial harmony. Black elders know that the potential for America’s most insidious racism to bubble to the top is always there, as they watch history repeat itself throughout their lives. In 2016, while many Americans thought Donald Trump’s history of racist actions, words, and behavior, which he has denied are racist, made him unelectable, Nicole’s grandmother sat with a watchful eye. "She knew Trump would be elected," Nicole says. "She knows white America."

Mi’Shaye, 22, a recent graduate of California State University Stanislaus who founded the Black Student Union on her campus, also has a grandmother who knows white America. Mi’Shaye, raised by her grandmother, lost her father to police violence in 1999 when police officers mistook her father’s cell phone for a gun. No charges were brought against the officer responsible. Mi’Shaye and her grandmother share an unimaginable grief, which has disillusioned them both toward any kind of racial harmony propaganda.

“[My grandma] warns me to be safe and to be careful. She knows the reality of how things really are,” Mi’Shaye says. “She doesn’t really ever say things are better now. She just wants me to be OK.”

Conversations with Black elders can provide insight beyond that of our most prominent news sources. But for all its anguish, they can also be a source of healing; a meeting place for grief, trauma, insight, hope, and joy. Thea Monyeé, a licensed marriage and family therapist who works with young people experiencing intergenerational trauma, believes that while my grandfather granting me permission to grieve is important and that commiserating over shared pain is powerful, the conversation does not stop there. She is wary that a focus on trauma obscures Black intergenerational joy and renders Black progress invisible.

When we see historical repeats such as these, it is not that Black America has not evolved or grown, it's that white America is stuck.

“Trauma shows up as Black elders taking culpability for what is not theirs. America takes no responsibility for our pain, so we take responsibility for everything,” she says. She points out that even in the midst of the protests, she sees Black people creating, and innovating, and sharing joy. “When we see historical repeats such as these, it is not that Black America has not evolved or grown, it's that white America is stuck. That is not for your grandfather to apologize for. You are a living reminder that Black people continue to progress.”

My grandfather still holds space for possibility. “You are the voice of a generation, your writing is a gift, and your insight will shake the world,” he told me. “You are the change. You are the revolution.” He spoke not of a future where white people finally recognize Black humanity, but of the possibility for me to become all that I imagine. That is the power of intergenerational connection. Our grandparents remind us we will not just survive, we will thrive. We are because they were. And we will become because they believed we could. In a moment of grief, I find solace in my grandfather’s belief that I am the transformation.