This Breathtaking Virtual Reality Video Of Nepal Will Move You To Make Change

One year ago, in April 2015, the world shook.

It shook for what seemed like an immeasurable amount of time under Kathmandu, Nepal.

Following the main event, which measured in as an 8.1 magnitude earthquake, the ground continued to sway for days, with aftershocks coming in nearly every 15 to 20 minutes.

The quake killed over 8,000 people and caused an avalanche on Mount Everest, taking an additional 21 lives.

In the immediate aftermath, it appeared the entire world came together in not only grief, but also as a collective unit to help the people of Nepal. But like all tragedy, soon, everyone must try to get back to normal life.

After months of aid, the world slowly backed away and returned to their daily routines. But the people of Nepal still need your help.

Journalist Christian Stephen, along with production team FS Productions, traveled to Nepal with the organization A World At School to shine a light on how the devastating earthquake continues to rock the future for the people of Nepal.

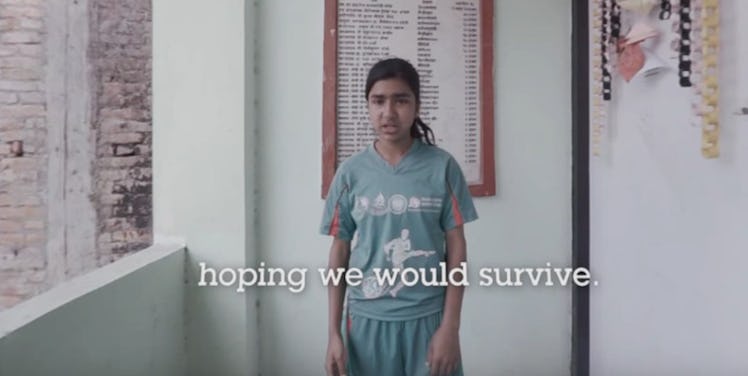

While there, he was able to capture a true story of hope with the children of Nepal who are willing to do anything just to get to school. Christian did so in stunning virtual reality to help you, the viewer, feel it all for yourself.

We asked Christian a few quick questions about why he chose this project, and why now. Find his Q&A below and his unbelievable video above.

Tell us a bit about your time visiting Nepal.

I first visited Nepal on the back of a two-month trip to Afghanistan, Central African Republic and Iraq -- so, I was ready to collapse and hide from work for a good while when the earthquake hit. In the space of six hours, I went from watching the news with my business partner, Dylan Roberts, and me saying that we ought to be there but we're looking forward to going home, to having a ticket to Kathmandu a few hours later. The destruction was staggering, and for some capricious reason, there's always a still small voice in the back of the mind when a story must be covered. So my first visit to Nepal was almost exactly a year ago. Flying into the deluge and seeing the aid planes bludgeoning each other to get the best photo op of who was saint aid worker number one. The following week, there revealed a resilience in the people and a stripping back of the hypocrisy of global, tar-drenched charity organizations. So, without sounding saccharine, Nepal has been on my heart heavily since then. The Nepali people deserve better, and there's honor in the rubble if you look with the right eyes and leave motive and Western arrogance at the door.

VR is really a new genre of filmmaking. Why do you think it's such a powerful storytelling tool?

I first used VR in Aleppo, Syria. So it was actually an annoyance to me in the thought process of 'the only thing that will bring fresh attention to this conflict is if I use this gimmicky fad that preys on the part of us all that wants to have the newest toy in fifty flashing colors,' and I'm still skeptical of the medium. However, as the months pass, I see the VR world shift from its initial knee jerk pandering to the pleasure dosing the market would be assumed to crave and further towards the search for a deeper, immersive understanding of the world we live in. So, as a tool, I see its double-edged blade. But just because it has the ability to dumb us down, is also the exact reason it must be harnessed for the stories in the world that deserve its power. There's honor in that, I think.

What was it like to walk away from Nepal at the end of the shoot?

The crushing internal terror that every director has at the end of a shoot -- especially of this sort which consists of crippling self-doubt and guilt that not only did you not get everything you envisioned, but also that you did the story a disservice. Luckily, as with most of these types of shoots, the following weeks tend to strip away the paranoia and give way to the actual important component far above self-analysis and filmmaking vanity: How can we serve the story? So, the post-Nepal atmosphere was far more quietly intense than most shoots, simply because the weight of the story sat heavily on each story. That and the beautifully surgical realization that whatever happened next was irrelevant, save the need to deliver something that executed the message of the film. That all sounds like intellectual bollocks, but it's the best way I can surmise it. The film isn't about anyone who created it, it's all about the kids.

A lot of your work, beyond Nepal, focuses on some very difficult topics. Why, as a young person, do you feel these are the stories that are important to tell?

I became a war photographer/conflict journalist/conflict correspondent (whatever it's supposed to be called) because I needed to see the raw nerve of what makes us tick. And again, after the initial, devastating rush of war and death, I learned the most important lesson so far of journalism: It's not about you. It's not even about the reader. The work, and the sacred charge of journalism, is to go where no other will and simply speak with those who have abandoned hope. Because through that act and that mission, we are all saved. By giving a voice to the voiceless, all of the dirt and blood and airstrikes are justified. Any difficulty in reaching that story fades once you see the face of someone who has, for even a short time, not felt forgotten. Mostly, I do it because by making people feel less lonely, I myself am able to prove to myself that I am not alone. It's an effort to locate myself in the world and be as useful as possible. Could all be hot air, but it quickens me. And that's enough.

What was the most difficult, and most hopeful, thing you saw on your journey?

The most difficult part was a woman called Indira, who rescues girls from sex trafficking and brothels. I hate to say that I'm a little jaded with the last five years of reporting, but sometimes, it's hard to connect. Indira devastated me. Thoroughly. It's rare to find altruism in any measure, let alone determined and vulnerable forms of it. She's incredible in every way. Completely sacrifices her life for the sake of girls pulled into the darkness.

Don't stop caring just because the story is over. As A World At School points out, globally, there are 80 million children around the world whose education has been disrupted by conflict and natural disasters. Help them gain the education they so desperately crave by clicking here.