Your IUD Might Be At Risk As Abortion Rights Disappear

This isn’t looking good.

On June 24, the U.S. Supreme Court officially announced its decision in abortion case Dobbs v. Jackson — and overturned Roe v. Wade, sending shockwaves throughout the nation’s reproductive rights landscape. As more and more anti-choice state legislatures move to either restrict or ban abortion care services outright, people all over the country are concerned about how these laws could affect other aspects of their reproductive freedom — especially when it comes to contraceptives. So, will some types of birth control, like IUDs, be banned now that the constitutional right to abortion is gone? Here’s everything you should know about laws that may affect your approach to contraceptives.

While as of July 2022, no state or national bill has been introduced to explicitly ban IUDs, the concern is very real. “So many of these anti-abortion laws are written by people who don’t really have a comprehensive understanding of reproductive health, pregnancy, or medicine in general,” says Cathren Cohen, a scholar of law and policy with the UCLA Law Center on Reproductive Health, Law, and Policy. Oftentimes, she notes, lawmakers will write restrictive anti-choice laws based on medically incorrect ideas and definitions — while medical professionals define pregnancy as the implantation of a fertilized egg within the uterine lining, many lawmakers have defined “pregnancy and life as beginning at conception, or fertilization of an egg,” Cohen says.

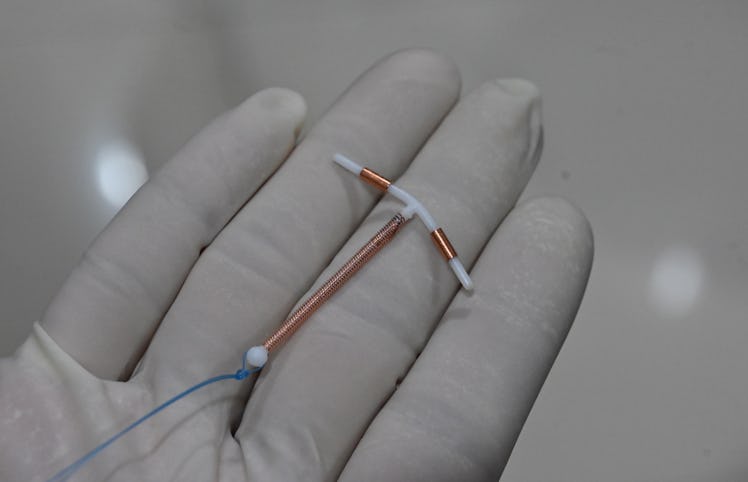

This is where things get tricky: Under laws defining fertilized eggs as pregnancies, IUDs could be illegal. An IUD, or an intrauterine device, is a small T-shaped device inserted into the uterus through the vagina to prevent pregnancy. While some release hormones intended to prevent pregnancy, copper IUDs are hormone-free. According to the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR), both copper and hormonal IUDs primarily prevent pregnancy by stifling fertilization, which occurs when a single sperm penetrates an egg. However, in the rare cases that fertilization does occur, IUDs might have the secondary effect of preventing implantation, which happens when a fertilized egg attaches to the uterine wall.

Because of this, IUDs could become illegal in many anti-choice states with overly broad abortion laws. For example, take Louisiana’s HB 813, which defines “personhood” as beginning at fertilization; under this bill, anything that prevents a pregnancy implanting could, technically, be considered abortion. Meanwhile, anyone who had an abortion under the law — which, thankfully, stalled in the state legislature in May 2022 — could potentially be charged for homicide.

It’s not as far off of a reality as some may think: According to a 1973 to 2020 study from the National Advocates for Pregnant Women, pregnancy loss or endangerment has been a key factor in more than 1,700 arrests or other legal actions taken against pregnant people. And as of June 24, when the Supreme Court overturned Roe, some medical professionals have reportedly begun refusing to prescribe certain medications that could potentially cause a miscarriage to pregnancy-capable patients, for fear of facing legal repercussions.

“That is a reflection of this chilling effect of these overly broad laws,” says Cohen. “A lot of these laws are written without the medical understanding of the way that birth control functions or different medications function.”

Cohen notes that the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe doesn’t do anything to directly affect contraceptive access on paper. “Nothing in the decision is immediately going to cause birth control to not be protected,” she says. However, birth control rights, guaranteed by the 1965 Supreme Court case Griswold v. Connecticut, may be on some shaky ground. In his concurring opinion in Dobbs, Justice Clarence Thomas stated that, since the arguments behind the original decision were “erroneous,” the court “should reconsider” its past rulings codifying rights to contraception access, same-sex relationships, and same-sex marriage. This is, uh, alarming, to say the least.

It also opens the door for states to attempt to limit contraception, particularly in the absence of any national bill confirming the right to birth control. On July 21, a bill affirming the right to contraception passed the House of Representatives, but it faces an uphill battle in the Senate. Not to mention the fact that nearly 200 House Republicans voted against it.

Birth control is particularly at risk for being subject to a state ban “because of the specific tie to the right to privacy” that Roe was based on, Cohen says. Anti-choice advocates, she adds, have vocally opposed contraception for decades. “Folks who oppose access to abortion [often define] IUDs or Plan B as causing an abortion, when [they] don’t,” she says. “It’s tied in these people’s minds as forms of health care they don’t want people to be able to access.”

However, as bleak as things may seem, Cohen highlights how there are still ways to overcome these stringent anti-choice laws. “There are so many states, particularly in the Midwest and Southeast of the country, where — even before [SCOTUS] overturned Roe — these states had such restrictive abortion laws, that there was either a single abortion clinic or no abortion clinic,” Cohen says. That’s why, she explains, it’s important to support grassroots organizations that have already been working to expand abortion access for decades.

“It’s really important for us to follow the lead of folks from places who have been living in a ‘post-Roe’ reality, even before Roe was overturned,” she says. “They have [already] been faced with this, and they have a good model for us to follow.”